Where Gumbo Was #432

New York has a lot of hidden waterways, their locations remembered only in random street names. Buried over the years, roofed over for sewers, diverted to fill in the shore—or, in the case of a select few like Newtown Creek, hidden in plain sight.

Most native New Yorkers—except those who've lived near its unpleasant shores—don't think about it, don't know much about it, and have seen it mainly from highway bridges crossing it.

Among the businesses operating along the creek, for over a hundred years, was the Van Iderstine Company, which collected butchers scraps and dead animals for the whole city and rendered them into industrial lubricants and fertilizer. You could smell it from the bridge about the same time you saw a row of peaceful cemeteries... many New York kids made a false assumption.

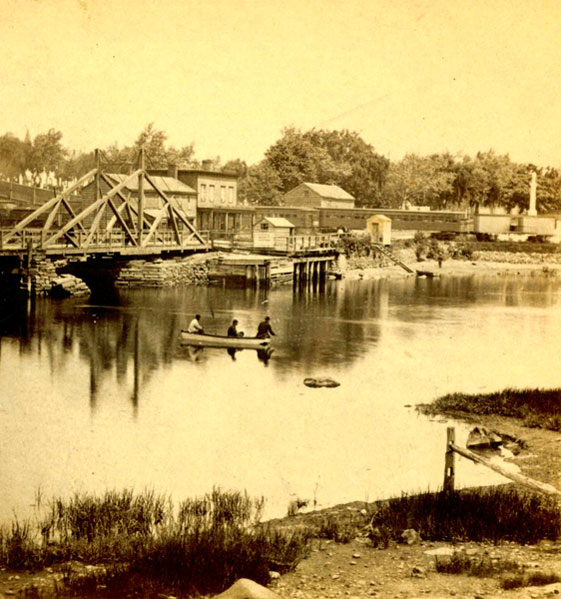

If there were a crime called 'creek abuse,' Newtown Creek could claim to have been one of the worst victims. When white settlers first arrived in the 1600s, it was a clear creek flowing through meadows, fed by other nearby streams and flowing out into the East River—prime hunting and fishing areas for local natives.

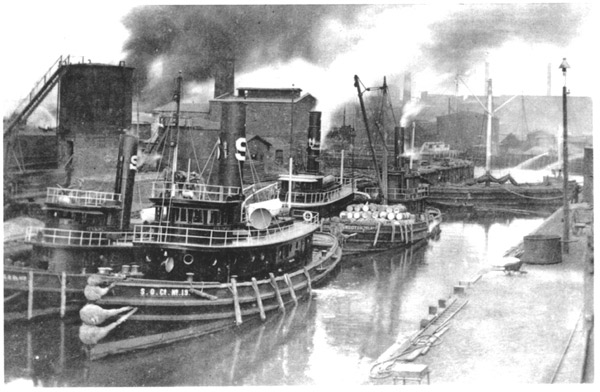

By 2010 when the Federal government added it to the Superfund cleanup list, it had gained a reputation as the most polluted, most toxic waterway in the U.S. Starting in the 19th century, industries built up along its banks, tossing their refuse into the slow-flowing waters, and shipping their products out by it. And, when convenient, cutting off and filling bits.

It's almost a miracle that the creek survived at all; it has a layer of congealed sludge at its bottom that's 15 to 25 feet thick in many places. The creek is along the border between the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens; both used it as a sewer (and in big storms, still do).

Newtown Creek was one of the earliest centers of oil and gas refining, starting in the 1840s; nearly all the major oil companies of today still have facilities along its shores, mostly for storage and distribution. In 1978, the Coast Guard found an oil leak in the creek; it turns out to go back at least four decades, during with the companies ignored it. Efforts since then have failed to either clean it up or completely stop it; over the years it has leaked over 30 million gallons—more than three times the size of the Exxon Valdez disaster.

A bronze marker shows the early 20th century locations of industries along the creek. Though most of them are gone, their traces remain.

Even today, some of the land along the creek is unusable; the Postal Service bought a tract a few years ago that had been used by a copper smelting plant. When they prepared to build, they found so much heavy metal contamination that they sued to force the seller to take it back and clean it up. The cleanup still hasn't happened.

The long walkway into the Nature Walk opens out to a plaza along the Creek

So, by now, you're probably wondering why all this is in a travel blog, and why anyone would want to visit or even know about it. And what all those pleasant green pictures in this week's clues have to do with it.

And the answer is because all the attention focused on it in recent years has led not only to Superfund status and one of the world's largest waste-treatment facilities, above, but also to the opening of a Newtown Creek Nature Walk along the Brooklyn shore.

That's where Gumbo was hanging out last week, and that's where he was found by George G, even though it's quite new.

The nature walk, which opened a few weeks ago, twenty or so years after it was proposed, was built as part of the deal that allowed the city to expand the Newtown Creek Wastewater Plant. It skirts part of Newtown Creek and takes a turn to follow a tributary called Whale Creek, most of which was filled in when the plant was built.

It includes native plants otherwise long gone from the area, access for kayakers (although few would want to kayak in Newtown Creek), seating areas and bits of the area's history. At its far end, it comes to the huge 'digester' eggs of the plant. There's even a visitor center and tours at the plant, but that's off the table for now because of the pandemic.

At that end, past the gates, you can step out into what's clearly trash central, streets lined with recycling companies, storage yards full of streetside garbage bins and large machines moving scrap of various kinds around.

Many nature walks and parks offer us a chance to escape the 'civilization' of the city around us; the Newtown Creek Nature Walk reminds us of the cost we've paid for civilization, and asks us to consider that perhaps more careful use in the past could have served us well—and that it can in the future.

A lot of the traffic along the creek these days involves not only heaps of scrap, but vessels working on sanitation. The MS Hunts Point, above, is one of three new sludge tankers operated by the Sanitation Department. They carry 5,000-ton loads of 'partly dewatered waste' (sewage sludge to you) between plants like Newtown Creek and others around the city where the decomposition process is completed. Up to 20 years ago, it was simply dumped in the ocean.

Also based in Whale Creek, next-door to the plant are a small fleet of ships like the Shearwater, below, which lower a conveyor belt into the water to capture surface waste and bring it up into its tanks.

And, at the end of the walkway, there's a table carved with a diagram of the Civil War ironclad, USS Monitor, built along the Brooklyn side of the Creek. Below it, a column showing the composition of a soil sample core drilled as part of the plant's construction.

If you're visiting: Best reached by car, to Paidge Avenue and Provost Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn; Greenpoint Avenue is the nearby main street. On foot, it's about a 15-minute walk from the nearest subway station, Greenpoint Avenue on the G train.

Comments (0)