I’m not a relentless walker. Distances vary on each trip, sometimes because of time constraints or weather or simply how it’s going for me physically. I long ago gave up pushing myself to keep a schedule if I simply don’t feel like going on. The landscape through which I walk will still be there when I return and enjoying myself is paramount.

I returned to England in the spring of 2016, my 5th visit to have included several days devoted to walking along the 184 mile long Thames Path. The first section I’d walked was from the Source of the great river, a trickle in the Cotswolds, to Oxford. the next visit began at Oxford and ended in Henley-on-Thames. Then came Henley to Taplow and, finally, Taplow to Hampton Court where this year’s walk would begin.

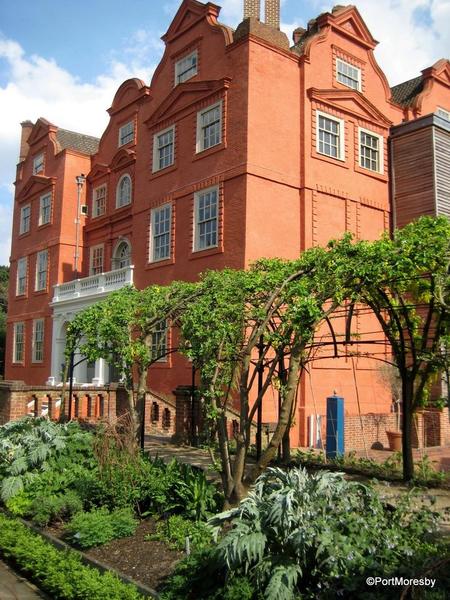

On the 3rd day, I arrived at Kew Palace in the afternoon, after beginning where I’d left off the day before at Richmond Bridge. This section of the path draws a line between the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and the river, as it flows north for a time before looping generally eastward toward London.

Unlike Ham House which faces the Thames several miles upriver, the orientation of Kew Palace is away from the river, its main entrance on the south side facing Kew Gardens and the Queens Garden on the north river side. It was from that perspective from the path that I first saw Kew Palace across the garden wall.

The Queen’s Garden between Kew Palace and the River Thames

What struck me most about what was called the “Dutch House” was how un-palace-like it seemed, small and comfortable, a place in the countryside for privacy and to escape ever-present duty in London. I couldn’t help being reminded of the suggestion that for generations, with some exceptions, the British royals have been seen by many to embody the values of their middle-class subjects more than of aristocrats. It became a royal residence about 1728 when it was leased for Frederick, Prince of Wales, George III’s father, when he arrived in England from Germany at the age of 21. Frederick had a separate wing built to house kitchens, household offices and staff accommodations, the ‘Royal Kitchens,’ which have been open to the public since 2012.

For decades the house was used to house royal children and as a schoolhouse for them. During George III’s periods of “madness” beginning in 1788, the house was used by Queen Charlotte and their daughters while the King was kept in nearby White House and later in a now demolished wing of Kew Palace. Queen Charlotte died there in 1818 and King George in 1820 at Windsor, where he’d been confined during his last 10 year recurrence of illness. The house was used periodically until 1844 and was finally given to Kew Gardens in 1898 by Queen Victoria. In 1899 it was opened to the public and remained unchanged for 97 years, thus making possible the accurate restoration, beginning in 1996, to reflect the time frame during which it was used by George II and Charlotte. Kew Palace reopened in 2006.

The interior photographs show a recreation of the second floor of the house,

about 1803 to 1805 while occupied by George III and Queen Charlotte.

The King’s Dining Room

The Queen’s Bedchamber

The Queen’s Drawing Room

Below, "The brown tin tub found stashed away in a chimney opening was the bath in which King George III took regular soakings in hot water, a prescription to calm him as he and his attendants wrestled with his terrifying bouts of mania." (Read the entire fascinating Guardian article here.)

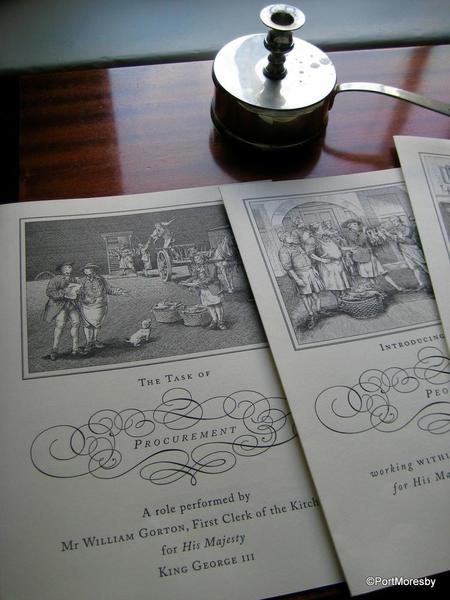

Upstairs, the Office of the Clerk of the Kitchen,

responsible for all household expenditures.

A fascinating finale to a visit to Kew Palace is ascending the stairs to the third floor where Princesses Amelia and Augusta, the unmarried daughters of George and Charlotte, lived until their mother’s death in 1818. The rooms were then closed and only reopened to the public in 2006, providing visitors an unrestored glimpse into their royal lives all those years ago.

Information for a visit to Kew Palace:

www.hrp.org.uk/kew-palace/

Next week, my favorite things in Kew Gardens.

Find all episodes of ‘PortMoresby in England’ here.

Comments (2)